Christopher Woodward, Garden Museum Director

Lambeth Green is a masterplan to connect the Garden Museum to adjacent green spaces, from the riverside of the Thames to Old Paradise Gardens and the arches of the railway beyond. But where – and what – is Old Paradise Gardens?

In this article we introduce one of Lambeth’s oldest but most overlooked green spaces – and one which we hope will become the heart of a new green quarter in years to come, working in partnership with Lambeth Council and our neighbours in Lambeth Village to deliver a masterplan by Dan Pearson. The community’s victory over developer u+i’s scheme for half-a-billion pounds of luxury high-rise flats – a decision recently held up in the High Court by order of Mrs Justice Lieven – has given the neighbourhood a chance to make a future of its own.

So, where is Old Paradise Gardens? It’s that patch of green which you glimpse across the road from the café, or just over the railings if you park your car on Lambeth High Street. You look across to the railway arches slowing into Waterloo; on two sides are the flats of the Whitgift Estate. It is not (yet) a postcard-pretty park. But it has an interesting past and is precious to our neighbourhood. One Sunday in April we will gather to sow a meadow for a third spring.

In 1703 Archbishop Tenison bought a garden on the site for £120 and donated it to the parish of St Mary’s. Lambeth was green and bright then, and a windmill turned on the High Street. But the churchyard of St Mary’s was clogged with coffins of the poor (the rich were buried inside; Tenison himself was one of the Archbishops discovered under the chancel in 2017). Tenison’s gift was to extend the churchyard. In 1814 the Parish paid £3,178 to buy more land (and £15 and five shillings on a feast to celebrate the extension).

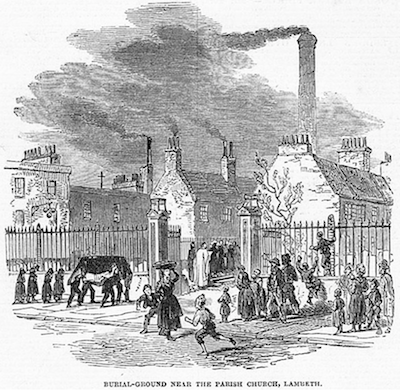

In the next few decades factories were built on the banks of the Thames, and the village became an industrial slum, blackened by smoke from the pottery chimneys. In the cholera epidemic of 1848 over a thousand parishioners died. The churchyard was full, and in 1853 closed. An old engraving captures a funeral of the time.

This is all described in an excellent book by Marie Draper, ‘Lambeth’s Open Spaces’ (1979), illustrated from the Borough Archives. There’s also a photograph of the Watch-House built in an elegant late Georgian style in 1825, to lock up drunks. Its outer walls still stand as an enclosure opposite The Windmill Pub.

Draper also sketches out the 19th century movement to promote the value of green space in an industrialised city, beginning with a Parliamentary Committee of 1833 which declared that workers ‘shut up in heated factories’ should be able to walk in the park on Sundays. The ‘Green Gym’ was a Victorian invention. Next came the Commons Preservation Society, founded in chambers in Inner Temple in 1865, with Octavia Hill as one member. Next, in 1882, the Metropolitan Public Garden Association, which continues today, and whose AGM we are proud to host each year (at its foundation it included ‘Boulevard’ in its title and next year I might stick my hand up and ask if it can be put back; in an age of road rage and Deliveroo we need our boulevards back).

But the serious point is that green space does not just happen. Green spaces exist because they are fought for with placards and petitions, or because of rare moments of vision, such as Regent’s Park, or the 2012 Olympic Park. One of those leaps of vision was the Metropolitan Open Spaces Act of 1881, which empowered vestries to spend money on turning derelict, closed churchyards into gardens, and Old Paradise Gardens was the first. Trees were planted and paths laid out to a landscape architect’s design. And gravestones stacked against the wall (like chairs cleared away after a dance, says Elizabeth Bowen in ‘The Death of the Heart’, putting her finger on why I, at least, find that Victorian solution depressing).

In 1979 Draper described the site as ‘dingy’ but a few years later the site was expensively landscaped, with an avenue of rubinias (which have lost their shape, and in a winter’s mist leer at you like a scene from Gormengast) and the mound on which our meadow will soon flower again. In 2012 a fountain was added, and more recently Matt Collins, our Head Gardener, has planted this up as a dry garden inspired by Oliver Filippi. And on Fridays we lead a small gardening club in raised beds. OPG (as we call it) is a park whose value adds up one visit at a time: a glimpse of an admired lurcher, a child playing hop scotch, a refuse worker relaxing on a bench, face tilted to the winter sun.

It was also the inspiration for Katie Spragg’s ‘Lambeth Wilds’, with young people picking flowers from brick crevices (see film below). They also looked at the watercolours in our collection by James Sowerby, the Lambeth botanical artist who was buried there in 1822. Sowerby devoted years, and hundreds of assiduous walking miles to Flora Londiniensis, the publication with William Curtis which recorded the flowers, wild or cultivated, which grew within a five-mile radius of central London. That book will be one inspiration to Dan Pearson in the future design; by happy coincidence Dan’s studio is on the same spot as where Sowerby’s painting studio once stood.

That illustrates, I think, how a space as tough and trodden as OPG can spring back into health and joy. Last year OPG was awarded a Green Flag for the first time. We will soon be able to share with you the design for a medicinal garden to be shared between our neighbours and the Museum’s learning groups. And if you park your car on the High Street for the Spring Plant Fair on 24 April you may see beds for planting being dug into the pavement in our partnership with Lambeth Council’s Highways Team. Small stepping stones towards a greener future.

—

Katie Spragg in conversation with community gardener Carole Wright and herbalist Rasheeqa Ahmad, a recent talk at the Garden Museum discussing the Lambeth Wilds project:

Christopher Woodward, Garden Museum Director