Guest curator of Lucian Freud: Plant Portraits Giovanni Aloi is the author of Lucian Freud Herbarium, a book which was recently reviewed in Hortus journal. We are delighted to share the review written by Rosemary Lindsay:

In the autumn of 2022 the Garden Museum will mount an exhibition of Lucian Freud’s paintings of plants. The curator will be Giovanni Aloi, author and curator specialising in the representation of nature in modern and contemporary art. In his introduction to Lucian Freud Herbarium he writes about Freud‘s position as a painter in the twentieth century, an overview of his oeuvre, and his contemporaries and friends in the art world. Aloi says ‘Freud’s paintings of plants, despite being exceptionally original, are still a mostly overlooked body of work in the troubled history of twentieth century art. While centuries of botanical illustrations and still life painting have objectified plants and focused on aesthetic appearances and symbolic meanings, Freud’s portrayals strip this encoding to the point that a plant’s enigmatic presence is revealed in all its glory. In his work plants are allowed to be what they are, irremediably engulfed in their laconic character and imperturbable demeanor.’ If this book is anything to go by the exhibition will be unmissable.

‘A History of Plants in Art’ is the second section of this scholarly and sumptuously illustrated book. Aloi writes about depictions of plants from a sixth century painting of a red rose from the Vienna Dioscurides to Monet’s waterlilies, the first truly modern paintings of flowers, and beyond. He talks about Cedric Morris, whose 1940 Group of Irises is illustrated, as Freud’s most influential teacher. Freud studied at Morris’s East Anglia School of Drawing and Painting and later acknowledged ‘Cedric taught me to paint, and more important to keep at it.’ In a final chapter on photography Aloi describes the celebrated Karl Blossfeldt’s 1928 book on plant photography, Urformen der Kunst (Art Forms in Nature), as ground-breaking. The last illustration in this wide-ranging and fascinating survey of plants in art is a delicate translucent digital print of Narcissus tazetta of 2014.

In the chapter ‘Lucian Freud’s Herbarium’, plants occur in many of his paintings that are not specifically plant studies; potted plants would appear in a portrait or an interior scene. ‘Plants have clearly been an essential component throughout Freud’s artistic development. In the Berlin family apartment where he spent his first eleven years…he grew up with reproductions of Titian and Dürer…and was fond of his Great Piece of Turf of 1503’. A photograph of Freud sitting in his garden in London gives a glimpse of an overgrown space where he planted things and let them grow untended. A buddleia seedling appeared and he painted it many times as it grew into a massive unpruned bush. His daughter Annie recalls that her father’s approach to gardening was ‘quite minimalist…he was not going to do any digging, ever’.

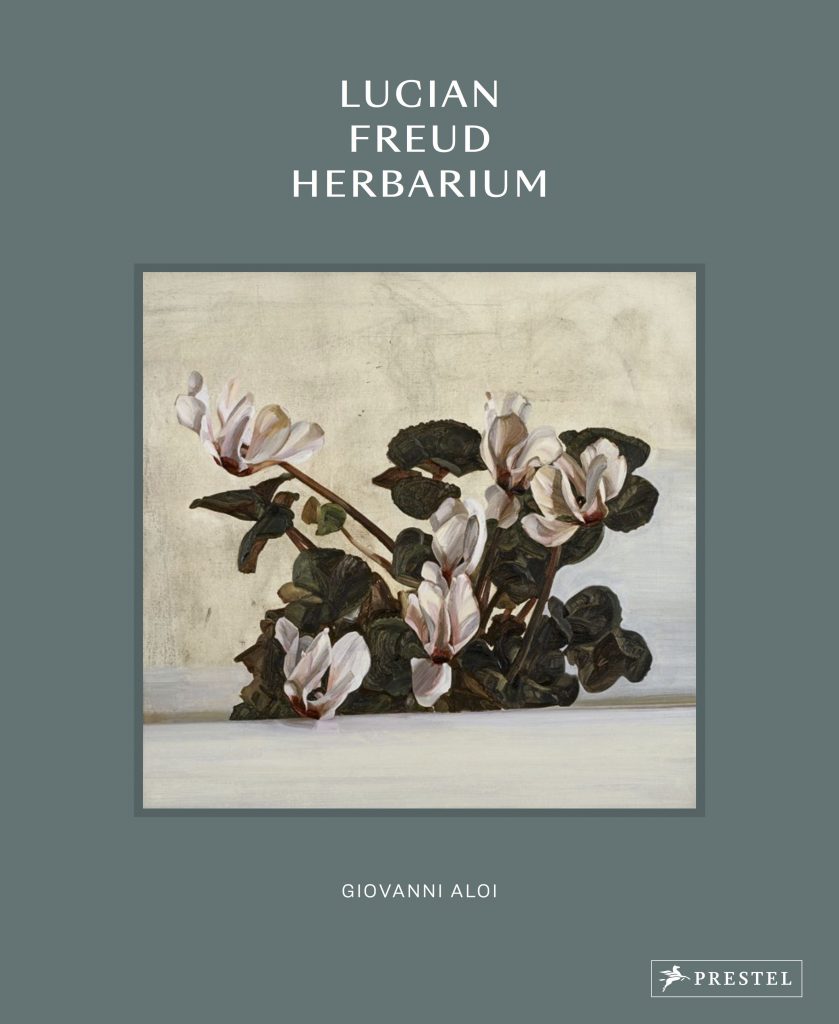

The plates follow, one hundred and eleven, and my one criticism of the book is the lack of an index of their titles. The works shown vary widely in techniques, media, size, and degree of naturalism or surrealism. Freud loved cyclamens; on the front cover of the book is his oil painting of a clump of C.hederifolium (1964); opposite the frontispiece is a photograph of him, young and handsome, with three huge cyclamen leaves and one bloom, sailing above him, wildly out of scale, the 1955 original of which floats across a chalky yellow plaster wall in his dining room at Coombe Priory. I keep looking through these plates with pleasure and awe. It is impossible to describe them all but I name a few in an attempt to give an idea of the range.

Still-life with Cactus and Flower Pots (1939), a naturalistic early oil painting of a cluttered shelf in the corner of a garden shed, with a view of a distant garden through the window.

Sea Holly (1945) in ink, wash, and crayon is a delicate literal drawing of the plant. It is followed by Scillonian Beachscape (1945-6), a large full colour oil painting of a stalk of the same sea holly, tall as a palm tree, on a flat beach, towering over a puffin perched on an egg-shaped stone, all set against a dead level dark indigo sea under a luminous sky – an eerily compelling picture.

Equally arresting is a viciously-armed Scotch Thistle (1944) lurching sideways across a full page, a magnificent full colour drawing. Man with a Thistle (Self-portrait) (1944) is shown nearby. Another painting I keep turning to is Daffodils and Celery (1946), two hefty daffs and one stick of celery in the top half of a scintillating glass jug shown against part of a chair, all at an odd angle. It’s an example of a group of ordinary things depicted in an extraordinary way by a genius. Five paintings of lemons follow where ‘Keen attention to detail, shadows, and shape imbue Freud’s lemons with an unprecedented gravitas.’ By way of contrast, a sprig of gorse, a split tomato, a huge bunch of bananas, a jug of buttercups, a box of strawberries, are all very much examples of botanical illustration in the traditional sense.

Freud famously worked slowly and the paintings of his garden, mostly in oil, in the later plates, are densely detailed, leaf by leaf, showing decidedly un-gardened, unkempt undergrowth, with an occasional glimpse of sunlight. Lastly are the etchings, mostly works from the late twentieth century. The detail is breath-taking. At the end is a double-page spread of a magnificent large etching from 2003-4, Painter’s Garden (68cm x 86cm).

In 2002, due to Freud’s admiration of Constable’s oeuvre, he was invited to curate an exhibition of his work at the Grand Palais in Paris. Included was Constable’s Study of the Trunk of an Elm Tree (1821). Freud created an etching of this work for the exhibition, Elm Tree, after Constable in 2003, ‘…therefore a humble homage to the dexterity of another master’s work.’ Giovanni Aloi also writes ‘Constable’s lifelike rendering of the tree’s bark and low branches, along with the detailing of moss and rotting wood, continued to influence Freud’s plant painting throughout his career’.

—