Jane Harrison, Project Archivist: Beth Chatto Archives.

In the many articles I’ve read about Beth Chatto and her garden while cataloguing her archive, there are certain questions which crop up again and again. When asked how her garden began, Beth always replies citing her husband Andrew’s research into the natural habitats of plant species as the basis of her ecological planting ethos. She also often mentions her friendship with Cedric Morris, which expanded both her horizons and her palette. The influence of these two men may have been the reason why she created her remarkable garden, but it could be argued that the reason that we’re still talking about her today is due to some of the women she knew, and their shared hobby of flower arranging.

It’s not hard to imagine why flower arranging became popular in the late 1940s and 1950s: the country was starting to rebuild itself after the war but resources were still scarce and everything from food to fabric was rationed. However, despite many gardens having been turned over to growing vegetables, there were still some decorative flowers and plants available and free to use. Constance Spry had already shown in the 1930s that beautiful arrangements could be made from a wide variety of plant material and in almost any container. Her work must have served as an inspiration, but the driving force behind the movement were women such as the redoubtable Julia Clements, who set off in 1947 to give a talk to the International Flower Show in New York wearing a blouse she had made from bomb-damaged net curtains and ended up giving an impromptu two-month lecture tour of the USA. Back in the comparatively dreary UK, she was asked to give a talk on her experience; part way through she dropped her notes and gave a flower arranging demonstration instead to show that it could be both an art and a source of pleasure.

Flower Clubs, and flower arranging competitions, began to spring up around the country over the next few years. At first glance it all seems rather sedate: ‘it can be helpful in the home and as a hobby, and a last line for the ladies to relieve the tension of everyday shopping’ was the verdict of the Mayor of Colchester, who opened the local autumn flower show in 1954. However, Stella Martin Currey’s description of the competitive nature of the 1955 Colchester Rose Show tells a different story. The scene she paints is reminiscent of modern craft shows such as ‘The Great British Bake Off’, starting with a mix of competitors racing against the clock to put together their carefully planned out exhibits, with an overseer watching for anyone bending the rules and calling surprisingly detailed instructions out over a loud speaker (‘Miss Brown has too many pansies in her exhibit, will she please remove three!’), and ending with exhibitors collapsed into the chairs on the garden furniture stalls while the judges inspect their work.

By 1955 Beth was one of these exhibitors, her award-winning arrangements specially noted in Currey’s article both for their design and for the unusual plants she used. Beth’s arrangements drew early recognition, and in 1952 she was invited appeared on the BBC’s afternoon programme ‘Leisure and Pleasure’, making several arrangements, including two live on air. Like many women, she used plants that came from her own garden; however, thanks to the Chattos’ interest in plants and their habitats, she had material to work with which many people hadn’t seen before. Despite her talent, Beth’s interest in plants might have stayed a hobby if it wasn’t for their neighbour, Pamela Underwood.

While Julia Clements opened Colchester Flower Club in 1951 and judged several of its competitions, it was Mrs Desmond Underwood (as she insisted on being called), a fellow founding member of the club and owner of Ramparts nursery, who encouraged Beth to take part and later to give her own demonstrations. Mrs Underwood was another formidable figure, specialising in growing silver foliage plants which she exhibited at Chelsea Flower Show at a time when entries were judged on the quality of the flowers. At first the reaction was not good; her plants were referred to as ‘Mrs Underwood’s weeds’. She persevered, and after several years won a succession of silver gilt medals for them, and finally two consecutive gold medals along with the Victorian Medal of Honour for her work.

According to Beth’s notes, in late 1953 she had a telephone call from Mrs Underwood to inform her that she’d booked her in to give a demonstration and lecture to open a new flower club. Beth described her reaction: ‘I shook with fright at the thought! but she (premonition?!) said it was time I looked beyond being mother of 2 small daughters and of course I could do it’. The event was a great success; Beth was able to combine her arranging abilities with a natural talent for presenting and was suddenly in demand as a speaker. This brought on further changes: while Andrew had driven her to the first few engagements, as they became a regular activity she decided to learn to drive so she could take her plants to venues herself. This was initially just material for her demonstrations, but after each session she would inevitably be asked where she got the plants she used, and she soon started packing the car with plants to sell, realising there was a market for ‘unusual plants’.

The move to White Barn House in 1960 and the development of the gardens there gave her scope for an even wider range of plants, and the space to think about starting a nursery to support the family when Andrew finally retired in 1967. There was already something of a customer base; flower clubs and their members were some of the earliest regular visitors to the garden and nursery and helped to spread the word around the country.

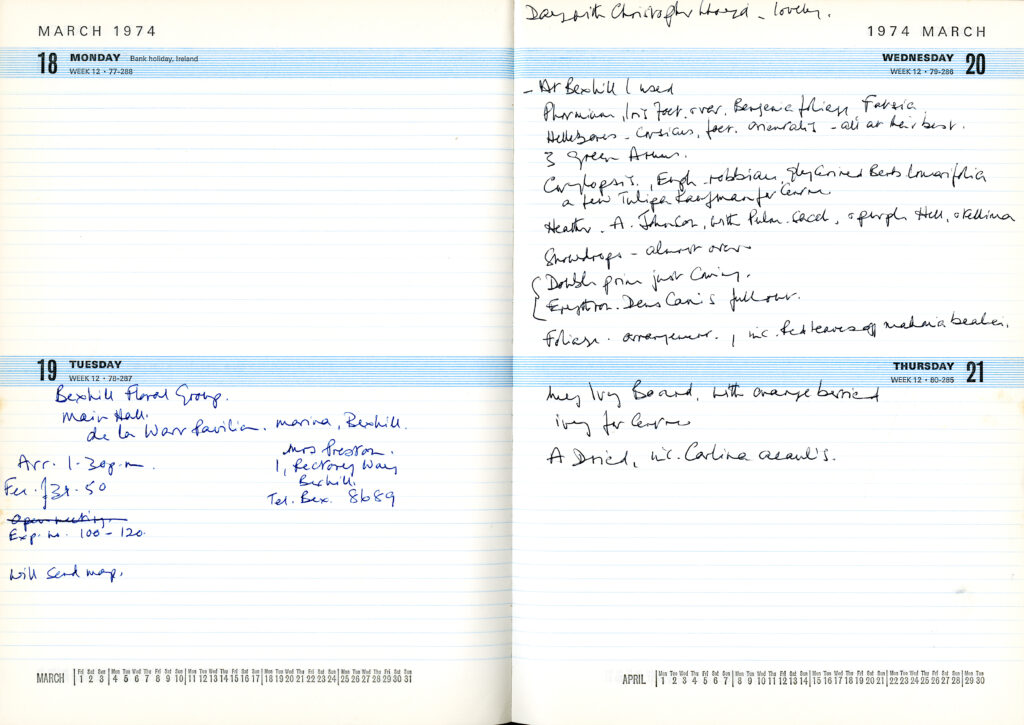

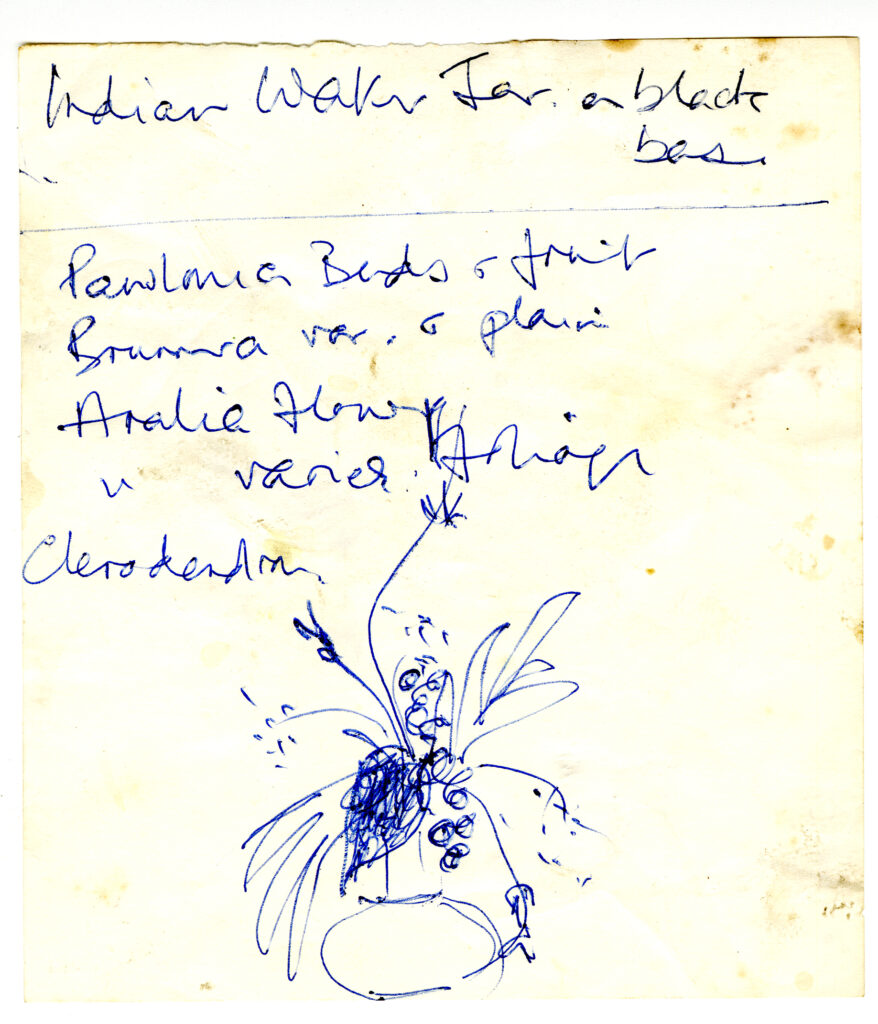

In addition to writing a column on her garden in the local newspaper, Beth worked tirelessly to raise the profile of her business through talks and demonstrations at flower clubs around the country. Her desk diary from this time, originally simply for recording appointments, gives an idea of how much work this might have been, with lists of arrangements and often a tally of which plants were sold.

Looking through the documents, it’s possible to see a slow shift away from flower arranging as a focus as the reputation of her garden grew and more people came to visit the nursery. For example, the talk she gave at a national symposium of flower arrangement societies in 1972, was entitled ‘Unusual Plants to Grow’; and focused on the cultivation of the plants as much as their use in exhibits, although it was still accompanied by an impressive list of arrangements.

Beth’s experience in flower arranging didn’t just give her the impetus to start Unusual Plants, it also gave her the chance to hone the design skills which are so apparent in the making of her garden and her award winning plant displays at Chelsea Flower Show in the 1970s and ‘80s. She was particularly interested in the Japanese tradition of flower arranging, with its asymmetrical triangles representing the relationship between Heaven, Man and Earth, and its idea of grouping plants which grow naturally in the same environment. This can be seen both in her flower arrangements and in the more permanent layout of her garden planting, with beds often having a somewhat triangular profile thanks to strong verticals. Her advice to aspiring gardeners in her 1975 catalogue talks about design as well as environment, summed up in the instruction ‘to plant in planned groups and not dotted like pins in a pin cushion’.

Although her later focus was on the garden, flower arranging remained a source of pleasure throughout Beth’s life. The archive has mentions of the arrangements she made for her own home and those of her friends, such as Christopher Lloyd at Great Dixter, and Countess Helen von Stein Zeppelin who asked for her help in decorating for her 80th birthday celebrations.

All of this leads me back to the question: if flower arranging had such an influence on Beth’s life, why does she rarely mention it when asked about the history of her garden and nursery? It may be that she simply didn’t feel she had much to say and might have given a similar response to the one she gave when asked to write about her extensive kitchen garden: ‘I wonder what I can possibly offer which does not appear obvious or elementary’. It’s clear that she always saw herself primarily as a gardener; but her career as an amateur flower arranger shouldn’t be discounted. It helped her hone her design skills, gave her a network of potential customers all over the country and gave her experience of competitions which must have stood her in good stead at Chelsea Flower Show. While its role may not be obvious it is hardly elementary.

All images are from the Beth Chatto Archive at the Garden Museum, © Beth Chatto Estate.

Notes

I started investigating Beth Chatto’s flower arranging thinking it would tie in nicely with the Constance Spry exhibition opening soon but was surprised to find that there is no mention of Spry in the Beth Chatto Archive. While I can’t imagine that Beth didn’t have at least one of Spry’s books, there’s no evidence the two ever met, even though they had friends at Benton End in common and both visited there at different times.

The title of this article comes from a conversation with Dr Catherine Horwood, Beth’s biographer, who said this was apparently one of the most common questions asked at her demonstrations, and also led to the name of her business.

References

The American Garden Guild Inc., The Complete Book of Flower Arrangement, (New York: Country Life Press, 1947)

Julia Clements, ‘The Art of Flower Arrangement’, article series in My Garden, No.184-215, April 1949 – November 1951

Stella Martin Currey ‘Talking to Women: Roses, lupins and the women who love flowers’, Colchester Gazette, 5 July 1955

Catherine Horwood, Gardening Women, their stories from 1600 to the present, (London: Virago Press, 2010)

Catherine Horwood, Beth Chatto, A Life with Plants, (London: Pimpernel Press, 2019)

Beverley Nichols, The Art of Flower arrangement, ( London: William Collins, Sons & Co., 1967)

The Times, Julia Clements, Obituary, 27 November 2010