By Matt Collins, Head Gardener

Driving the solitary highway connecting the city of Tucson and Wild Western Tombstone in Southern Arizona, you exchange one desert region for the beginnings of another, as the road subtly climbs in the direction of Mexico. The iconic saguaro and scattered mesquite trees of the Sonoran Desert soon peter out, giving way to the Chihuahuan’s architectural yuccas and agaves, in a landscape a little more sparse and flat, yet no less horticulturally hostile. Knitting these two arid expanses together like a mesh of barbed wire are great stands of strappy ocotillo cactus, and various chollas, with their fat caterpillar-like fingers clothed in clinging needles.

Over the stony ground, prickly pears creep low, pimpled with swelling buds. These, and many other fiercely armoured Southwestern cacti were what I had in my sights when visiting Arizona last month, along with the ephemeral wildflowers (Mexican poppies, rose-mallow, yellow hibiscus) that are thrust into spring bloom by rolling thunderstorms the previous autumn. The last plant I imagined encountering in this dry environment, therefore, was a rose beloved of the English garden: a relatively thornless climbing white Rosa banksiae sprawling over the backyard of a former Tombstone boarding house.

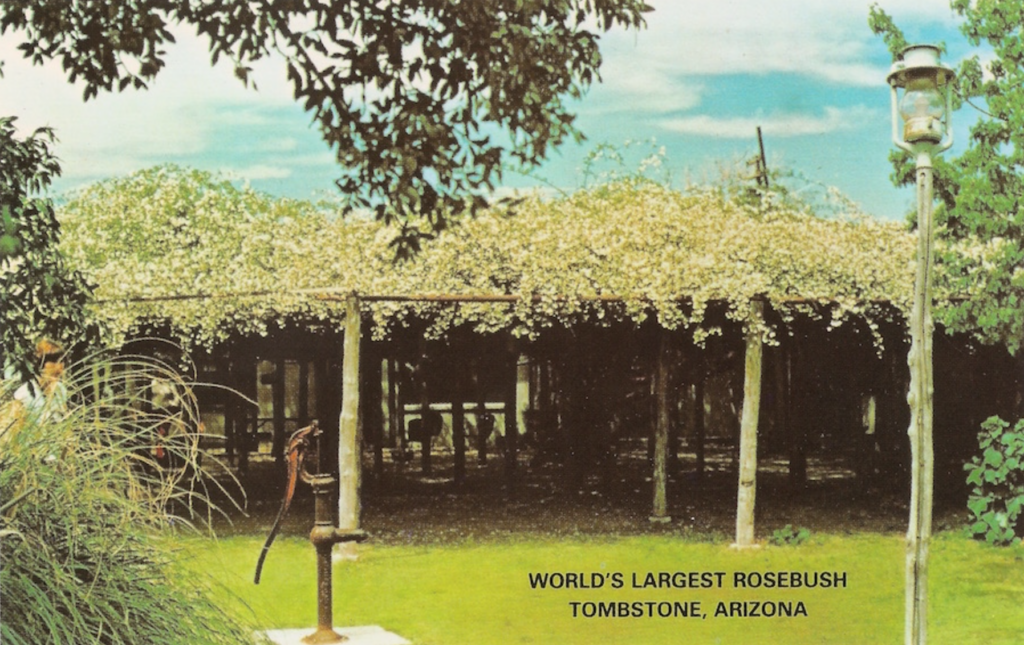

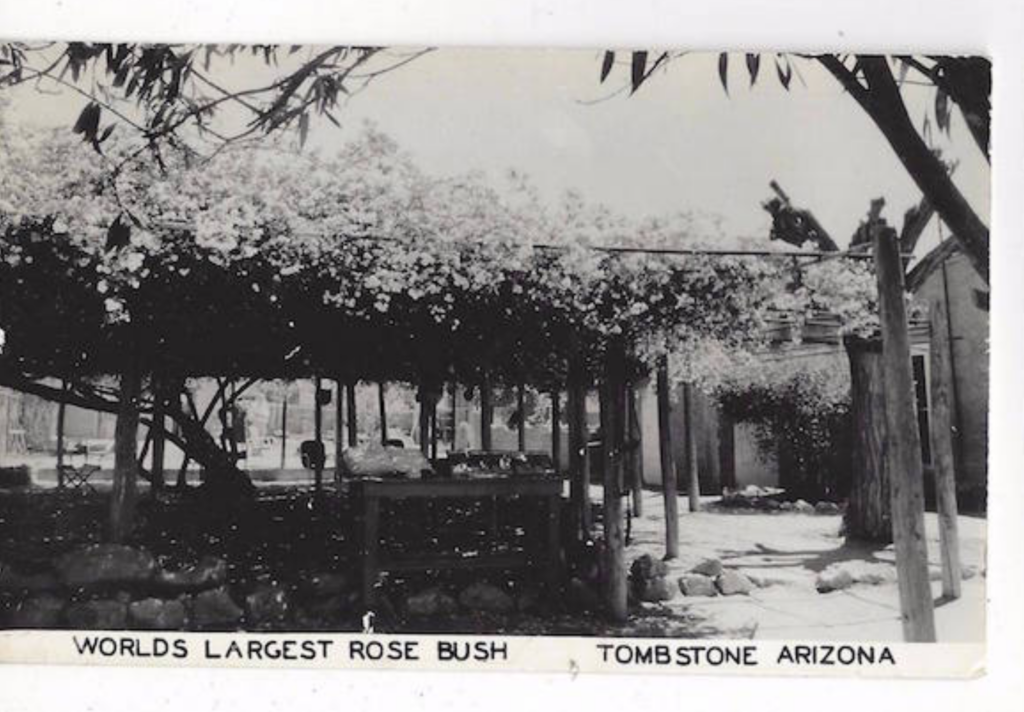

Sonoran Desert, photo by Matt CollinsHaving exceeded 8,000 square feet in reach, and with a trunk circumference of 13 feet, Tombstone’s ‘Lady Banks’ rose is not just massive but holds the Guinness World Record for the largest rose in the world. Its great tangled mass is supported upon a framework of head-height wooden struts and cross poles, and for roughly six weeks of the year — across March and April — showers of clustered white petals form something resembling a sunburst cloud suspended in air.

How the rose came to Tombstone, over 130 years ago, is the story of the former boomtown itself, arriving with European settlers joining the race to extract silver from the desert. Between 1877 and the mid 1880s, after the discovery of silver ore in the surrounding Cochise County, Tombstone flourished from a settlement of tents to a heady bustle of saloons, restaurants, opulent hotels and brothels, two banks and a bowling alley, with a population of over 10,000. It was at one point said to be the fastest growing town between St. Louis and San Francisco. Those travelling great distances to stake a claim or work for a profitable mining company in Tombstone might have found themselves at what is now Rosetree Suites, but formerly the Cochise Boarding House; somewhere affordable to lodge while raising the capital to build a house. This was the case for the miner Henry Gee, and wife Mary, who had journeyed from Scotland to the American Southwest shortly after marrying in 1884.

After a year far from home, for the most part alone in a rough and ready town already renowned for Cowboy and Western disorder (the famed Gunfight at the O.K Corral had taken place in 1881), Mary would no doubt have been overjoyed at the arrival of a large box of plants and cuttings sent from her family garden back home: heather, purple aquilegia, tulips, daffodils, and rooted cuttings of a white rose she had planted as a child. Against the inhospitable landscape backdrop of what was then still Arizona ‘Territory’, one imagines Mary cherishing these plants, and even the soil they came in, like family itself. As all gardeners know, a sense of place, and its memory, attaches to plants in a profound way. As a gift, Mary gave the boarding house caretaker, Amelia Adamson, one of the rose cuttings, and together they planted it near a woodshed in the backyard, where, against all odds, the plant thrived.

Adjoining Rosetree Suites, where visitors to Tombstone can take a room on a quieter street away from the horse-drawn tours and gunfight reenactments of today, is the Rose Tree Museum. Here, first floor rooms have been restored with authentic 19th century decor and fixtures, and curated to tell Tombstone’s fascinating history through the life of one of the town’s pioneer mining families. Outside in the courtyard behind, you can sit in the shade of the enormous rose tree itself, and, naturally, marvel at the tangled mass of its astonishing, gnarled trunk. It was a scorching spring day when I visited, but I’d arrived early enough in the morning to have the place to myself for a while. I was nearing the end of a hefty Arizona itinerary driving down and across the state, and still had jet lag whooshing in my ears, so to sit beneath the rose in filtered sunlight was a rare bliss. The season had been slow and so buds were only just breaking, but the chirping of sparrows, silhouetted behind the mat of criss-crossing stems, coupled with the sudden absence of car engines, was utterly serene: Mary Gee cannot have foreseen what an oasis she would create.

While planting roses at the Garden Museum recently, to chime with our current exhibition Wild & Cultivated, Fashioning the Rose, I enjoyed reading Michael Pollan’s reflections on accommodating roses at his garden in Connecticut. In his outstanding gardening memoir Second Nature, the American author likens the necessary ground preparations to getting the house ready for the arrival of a cantankerous, aristocratic old lady with pernickety tastes: “Her stay is bound to be an ordeal, and you want to give her as little cause for complaint as possible”.

Pollan recounts arduous double digging, and using up an entire supply of hard earned homemade compost in an effort to appease his demanding and sickness-prone roses. And this is the common experience, for whether your soil is clay, loam or sand, a level of moisture retention is near essential for establishing a healthy rose. How then, has the world’s largest rose ended up succeeding in the Chihuahuan Desert? This, too, might be attributed to the story of Tombstone.

By the late 1880’s, Tombstone’s silver mines has penetrated the water table and were experiencing underground seepage, resulting in water needing to be pumped out at increasing volumes to avoid the shafts flooding. A series of fires subsequently damaged expensive pumping systems, just as the Sherman Silver Purchase Act came into effect, which caused the price of silver to plummet dramatically. Staff were laid off and mines were closed, and water filled many deserted tunnels. By 1900, fewer than 700 residents were recorded as living in the town. Meanwhile, as the roots of Mary’s rose excavated downwards in search of sustenance, they are thought to have tapped into these cavities of resting water and struck gold of their own — a network of irrigation channels running wide beneath the desert scrub.

Furthermore, owing to the town’s sizeable domestic sewage system, which was modern for its time, there will have been a ‘healthy’ supply of accessible nutrients down there. As Tombstone declined, the rose prospered and, now a tourist attraction, welcomes visitors arriving to see the reassurance, through tourism, of ‘the town too tough to die’. Former mineshaft poles have been used to brace its burgeoning branches, beneath which sit rows of rooted cuttings, potted-up as purchasable souvenirs.

Rosa banksiae is native to China, and was introduced to European cultivation by William Kerr — another Scot — while working under Sir Joseph Banks at Kew in the early 1800s. It was named for Joseph’s wife, Lady Dorothea Banks, and is known commonly as Lady Banks’ rose. From the same region of China came the vast and vigorous Kiftsgate rose, a variety of Rosa filipes growing at Kiftsgate Court Gardens in Gloucestershire, which, at 80 x 90 feet, is said to be the largest rose in Britain. But after spending a year in the garden at Benton End in Suffolk, where grows the gigantic Rosa ‘Sir Cedric Morris’ (planted by the midcentury artist-plantsman as a found hybrid seedling), I wonder if the Kiftsgate might soon be overtaken… Cedric’s is currently the size of a house. In June, you can crawl beneath the low arch of the spindle tree it has swallowed and sit encased in a snow globe of flowers: one of my enduring memories of summer at Benton End.

These behemoth roses are magnificent beasts. With the world endlessly allured by the colours and forms of showy cultivated varieties, it’s good to remember the childlike wonder of wild roses you can disappear inside, and the curious places in which they thrive.

—